- Why State Exemption Laws Are Important

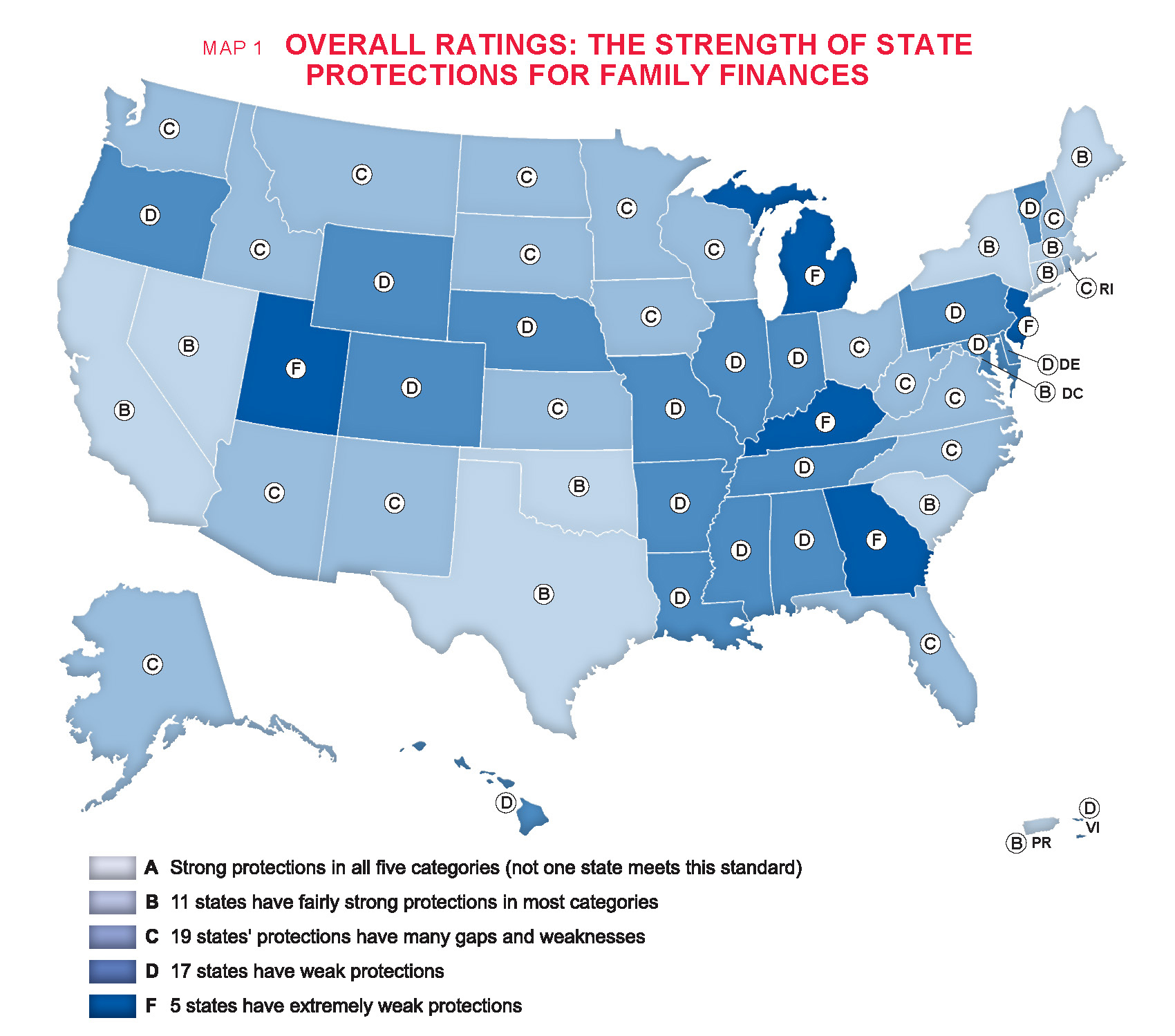

- Map 1: Overall Ratings

- Story: West Virginia Nurse Finds Bank Account Frozen in Midst of Pandemic

- Protection of Wages: Can a Creditor Reduce a Debtor to Below the Poverty Level?

- Map 2: Protection of Wages

- Story: Florida Father Hit with Wage Garnishment in Midst of Pandemic

- Stopping Creditors from Threatening Seizure of a Debtor’s Household Goods

- Map 6: Protection of Family Household Goods

Several States Made Progress Since 2020, but Much Remains to be Done

Recommendations

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

State exemption laws, which protect income and property from seizure by creditors, debt buyers, and the debt collectors they hire, are a fundamental safeguard for families. Exemption laws are designed to protect consumers and their families from poverty, and to preserve their ability to be productive members of society and achieve financial rehabilitation.

These protections are particularly important as families struggle to regain financial stability as pandemic protections expire. Yet not one jurisdiction meets five basic standards:

- Preventing creditors from seizing so much of the debtor’s wages that the debtor is pushed below a living wage;

- Allowing the debtor to keep a used car of at least average value;

- Preserving the family’s home—at least a median-value home;

- Preserving a basic amount in a bank account so that the debtor’s funds to pay essential costs such as rent, utilities, and commuting expenses are not cleaned out; and

- Preventing seizure and sale of the debtor’s necessary household goods.

This report details the extent to which states protect families in each of these five areas.

Best states:

Massachusetts, which modernized its archaic exemption laws in 2010, and Nevada, which also recently improved its laws, come closest to meeting these five basic standards, each rating a high B grade. Solid B states include California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Maine, Puerto Rico, and Texas, while New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina rate low B grades.

Worst states:

At the opposite end of the scale are several states whose exemption laws reflect indifference to struggling debtors. These states allow creditors—or the debt collectors they hire-to seize nearly everything a debtor owns, even the minimal items necessary for the debtor to continue working and providing for a family. Georgia, Kentucky, Michigan, New Jersey, and Utah are the worst and rate an F. Meanwhile, Arkansas, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming are nearly as bad, rating low D grades.

During the past twelve months, several states amended their laws to make improvements in these protections. Arizona, Connecticut, Maine, Montana, Virginia, and Washington made particularly significant improvements, and Georgia, Idaho, New York, Tennessee, and Utah also made positive changes. See Several States Made Progress for details.

Why State Exemption Laws Are Important

State exemption laws are a fundamental protection for families. Without these laws, once a creditor obtained a ruling from a court that a consumer owed it a sum of money, the creditor could seize the debtor’s entire paycheck, bank account, car, and household goods, and sell the debtor’s home. Exemption laws place limits on these seizures. They are designed to protect consumers and their families from poverty, and to preserve their ability to be productive members of society and to recover and achieve financial rehabilitation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the enormous gaps in the states’ exemption laws. Only when stimulus checks started going out to families’ bank accounts did many states realize that they had no protection for a basic amount in a bank account. As workers lost jobs and hours, states scrambled to institute moratoriums on wage garnishment, bank account garnishment, and collection lawsuits.

As the pandemic recedes, families are left with a mountain of debt. People struggling to get back on their feet are likely to face a wave of lawsuits for medical bills, back rent, credit card debt, the balance due on repossessed cars, and even utility bills. This will come at a time when most pandemic protections, such as the moratoriums on garnishment and foreclosure that many states and federal housing agencies adopted, have expired or are soon to expire.

Exemption laws are particularly important because they protect cars, work tools, and other property that consumers need to stay in the workforce. When individuals lose their jobs, the consequences fall not just on them and their families, but also on landlords, local merchants, and other creditors that the consumer might have paid.

Without improved exemption laws, garnishment and attachment will drain away the wages and resources that families need—and that the local economy needs them to be spending at Main Street businesses. Reform of exemption laws not only protects families from destitution but can also act as an economic recovery tool that will steer money into state and local communities. By protecting families from impoverishment, exemption laws also save costs that taxpayers would otherwise have to bear for services such as emergency shelter and foster care.

Exemption laws also deter predatory lending. Creditors are less likely to make unaffordable loans if they know they will have to rely on the consumer’s ability to repay the debt, not on seizure of the consumer’s essential property. The gaps in exemption laws also give debt collectors enormous leverage. By threatening to take a debtor’s essential personal property, such as the family car or household goods, a debt collector may persuade a debtor to use the money needed for rent or medicine to pay an old credit card bill that ought to be a much lower priority.

Exemption laws are primarily an area of state authority. Federal law requires employers to protect a small amount of a debtor’s wages from creditors: 75% of wages or 30 times the federal minimum wage per week. At the current minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, the federal protection does not even reach the poverty level, but states can protect more. In addition, federal bankruptcy law provides its own set of exemptions for debtors who file bankruptcy. However, states are allowed to opt out and replace the federal bankruptcy exemptions with their own, and many have done so. Moreover, since only a small percentage of consumers in financial distress file for bankruptcy,1 most distressed consumers depend on state garnishment and attachment rules for their protection. Accordingly, while this report includes some federal recommendations, it focuses on the laws that apply to debtors who do not file bankruptcy.

A full analysis of state exemption laws and their interpretation can be found in National Consumer Law Center’s Collection Actions (5th ed. 2020). An appendix to that book includes detailed summaries of each state’s exemption laws.

West Virginia Nurse Finds Bank Account Frozen in Midst of Pandemic

It was just a normal day for Preston County resident Cheri Long — or as normal as a day gets during a global pandemic.

Long, who works as a nurse at an assisted living facility, was at the store purchasing groceries for her and her family when her debit card was declined. She knew she had money in her account, so she began to look into what was causing her payment to be rejected. That’s when she discovered there was a lock on her bank account by WVU Hospitals due to unpaid medical debt.

This left Long and her husband Seth — who were otherwise in a situation to attempt to tackle the pandemic safely without incurring new debts — falling behind on their house payments and utilities, and struggling to provide themselves and their children with essential supplies to survive. At points, she had to bring home food from her workplace and ask for gas money from her co-workers.

“I can’t begin to explain the hurt and embarrassment I felt by the way I was treated when I called, begging in desperation to help me or lead me in the right direction so I could provide for my children while working as a nurse on the front lines,” said Cheri Long. I couldn’t even afford to purchase fabric to make myself a mask due to the shortage of personal protective equipment.”

Source: Excerpted from Joe Smith, Times West Virginian, “Hospitals in West Virginia are seizing bank accounts, garnishing wages, over unpaid debt during ongoing COVID-19 pandemic” (April 20, 2020)

Toxic Mix: How the Wealth Gap Creates a Bigger Debt Burden for Black and Latinx Families

The extent to which states protect consumers’ income and assets from seizure by creditors is particularly important for communities of color, as weak exemption laws build on, and widen, the racial wealth gap. Communities of color are disproportionately burdened by debt,2 and disproportionately subject to judgments in collection lawsuits3 and wage garnishment.4

These disparities are not surprising, given the country’s vast and long-standing racial wealth gap. The median income for white households in 2019 was nearly $70,000, compared to just about $44,000 for Black households, and $56,000 for Latinx households.5

Differences in assets needed to weather shocks are even more stark. When hit with challenging financial times, Black and Latinx households have less of a safety net to draw on. While white families have a median wealth of $188,200, Black families have just $24,100 and Hispanic families just $36,100.6 A typical white family has $8,000 in reserve for emergencies, compared to just $1,500 for Black families and $2,000 for Latinx families.7

Not only do communities of color have fewer assets to cushion financial shocks, but they are also more likely to experience those shocks or to have income so low that even small bumps are mountains. Black and Hispanic households disproportionately experience unemployment.8 While the poverty rate in 2020 was 11.4% for white households, Black and Hispanic households had much higher poverty rates of 19.5% and 17% respectively.9

The roots of these disparities can be traced in part to systematic, government-sponsored exclusion of Black families from homeownership opportunities, the most significant form of wealth-building and financial stability for most Americans. For example, when the federal government first embarked on a program of long-term federally-backed mortgage loans in the 1930s to enable Americans to become homeowners, it systematically excluded Black neighborhoods.10 Banks continue to deny credit to potential Black and Latinx home buyers at a much higher rate than potential white buyers,11 and Black and Latinx borrowers pay hundreds of millions of dollars more collectively on their mortgages every year, due to higher average interest rates.12

Not only do households of color have fewer resources to draw from, but often these households must spend more on everyday expenses as well. For instance, Black households pay hundreds of dollars more a year on their energy bills than white households,13 and families in predominantly non-white urban neighborhoods pay more for food.14 Black borrowers owe, on average, $25,000 more in student loans than white borrowers,15 and are charged higher interest rates on car loans and more for car insurance.16 Neighborhoods of color are also disproportionately targeted by predatory lenders.17

How State Exemption Laws Work

Exemption laws come into play when a creditor goes to court and obtains a judgment against a consumer. A judgment is a decision from the court that the consumer owes a specific sum of money. The creditor can then take steps to seize the consumer’s wages or property to pay the debt. Typically, the creditor asks the court or an official, such as a sheriff, to seize property (attachment), order the consumer’s employer to withhold a portion of the consumer’s wages (wage garnishment), or order a bank to pay the consumer’s funds to the creditor (bank account garnishment). The creditor can also place a “judgment lien” on the consumer’s real estate and then foreclose on that lien, forcing sale of the home.

The state’s exemption laws specify how much of the consumer’s wages and property the creditor can seize and how much it cannot seize. Limits on wage garnishment are generally self-enforcing—the law requires the debtor’s employer to be instructed to withhold only the non-exempt amount of the debtor’s wages, so the debtor does not have to take affirmative steps to claim this protection. In a few states, some other exemptions are self-executing. However, in many states, the property will not be protected unless the debtor takes various procedural steps—typically, filing papers in court or attending hearings—to claim the exemptions. These steps are often daunting for consumers, who are typically left to navigate the judicial system on their own without attorneys.

Many states provide earmarked exemptions for particular types of property. For example, Arizona exempts a home worth up to $250,000, a car worth $6,000, $300 in a bank account, and $6,000 in household goods. Other states provide a wildcard exemption—one that that the debtor can use to protect a variety of types of property. For example, Mississippi protects a home worth $75,000, but then provides a $10,000 wildcard exemption to cover the debtor’s car, bank account, household goods, and all other property. Since different debtors will choose to apply a wildcard exemption in different ways, it is hard to compare the level of protection that a state provides for a particular type of property. In this report we have therefore assumed that a debtor will apply most of the wildcard first to protect a family car, then to protect a basic amount in a bank account, and then, if any of the wildcard is left, to protect household goods. This approach standardizes the treatment of the wildcard and avoids double-counting it.

Because of inflation and changes in society, exemption laws can become irrelevant simply due to the passage of time. States can reduce the erosion of these critical protections by building in automatic inflation adjustments. Alaska is one example: the dollar amounts in its exemption law are adjusted by statute every second year to reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index. Laws in Alabama, California, Indiana, Maine, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, South Carolina, and Utah also provide for automatic inflation adjustments.18 It is surprising that more states have not adopted this simple, yet fair and effective approach.

Protection of Wages: Can a Creditor Reduce a Debtor to Below the Poverty Level?

Protection of wages is one of the most important roles of exemption laws. When creditors garnish a consumer’s wages, the employer is required to take the money from the consumer’s paycheck and send it to the creditor. The consumer never sees that money and cannot use it to pay higher-priority obligations, such as rent, food, and child care. Instead, the money goes to pay old credit card debts, written-off medical bills, or the amount still owed after a car was repossessed and sold. Year after year, the wages of about four million workers are garnished for consumer debts.19

Wage garnishment can doom a family’s efforts to stay afloat. In most states, an employer is even permitted to fire a worker whose wages are garnished for more than one debt.20

Since 1970, federal law has protected 75% of a wage earner’s paycheck or 30 times the federal minimum wage, whichever is greater. This means that wage garnishment will not reduce a debtor’s paycheck below $217.50 (thirty times the current minimum wage of $7.25 an hour). But a weekly paycheck of $217.50 places even a single individual who has no dependents below the federal poverty level.21 For a family of four, $217.50 per week is less than half of the federal poverty guideline ($509.62).22 Even if it were doubled, the federal minimum wage would still be far below a living wage for most families.23

Federal law gives states the option of protecting a larger portion of a debtor’s paycheck if they choose. Yet only eleven jurisdictions protect even a poverty-level wage for a family of four, and 13 jurisdictions do not go beyond the federal minimum at all.

Table 1 lists the states that fall into each category. See our Rating Criteria for details and our State Summaries for state-by-state information.

The best states:

Four states ban wage garnishment entirely for typical consumer debts:

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- Texas

These four states earn an A rating for protection of wages. Seven additional jurisdictions—Alaska, California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Florida, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin—at least prevent a debt collector from reducing a family to below the poverty level, and receive a B rating, though their protections may be insufficient to protect a living wage.

The worst states:

Thirteen jurisdictions—Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Ohio, Puerto Rico, Utah, and Wyoming—are rated F. They protect no more of a worker’s wages than the federal minimum: $217.50 a week, less than half the poverty level for a family of four.

Florida Father Hit with Wage Garnishment in Midst of Pandemic

On paper, Randall Ward would seem to be well-insulated from garnishment. He lives in the small town of Marianna, Florida, and state law protects the wages of anyone deemed the “head of household,” which is defined as someone who earns more than half the household’s income and has dependents. Since Ward helps care for his 20-year-old son with Down syndrome and a granddaughter, his pay from his job as a manager at a Waffle House is eligible for protection from garnishment.

But when Encore, after having won a judgment against Ward the previous year, sought to garnish his wages this past February, Ward didn’t understand that he qualified for the “head of household” exemption. So, starting in March, Encore began taking a quarter of Ward’s take-home pay. The size of the debt, a Citibank card that had ballooned to $5,220 with interest and court costs, meant that Ward, even with what he’s proud to call a “good job,” was in for many lean months.

The only way to make ends meet, he said, was to cancel health insurance for himself, his son, and his wife, “because I could not pay the bills if I didn’t do it.”

Then the virus forced his restaurant to close for several weeks and his pay stopped altogether. The family was without income as he waited for his unemployment claim to go through. When, finally, he could go back to work, the garnishments returned.

Source: Excerpted from Paul Kiel and Jeff Ernsthausen, ProPublica, “Debt Collectors Have Made a Fortune This Year. Now They’re Coming for More” (Oct. 5, 2020).

NCLC’s Model Family Financial Protection Act suggests protecting at least $1,000 per week (to be adjusted for inflation).24 If the debtor nets more than that amount but no more than $1,200 a week (the approximate equivalent of $70,000 a year in gross wages), 10% of the excess amount can be garnished. If the debtor earns more than that, 15% can be garnished. The model law thus allows creditors to make use of wage garnishment, but it protects a debtor from a disastrous reduction in the income necessary to meet daily expenses. In many states, $1,000 per week would be sufficient to protect a living wage, but states with high costs of living should consider protecting more.

A growing issue is whether wages retain their exemption after deposit in a bank account. There is no federal protection for wages once deposited. A state’s failure to protect wages after deposit in a bank account enables creditors to evade the protection of the consumer’s wages by going directly to the bank account and cleaning it out. This danger is increasing as more and more employers use direct deposit to pay their workers. Whether states protect wages after deposit—or, better yet, provide a general protection for a basic amount in a bank account—is discussed here in connection with our evaluation of state protections for bank accounts.

Protecting the Family Home from Creditors

Protection of the family home from creditors is one of the fundamental purposes of exemption laws. Loss of the home can mean a loss of support networks. It can also mean loss of a job if the family cannot find replacement housing within commuting distance. For a farm family, loss of the home means loss of their source of support. Losing the family home is particularly hard on children, as it often means that they must change schools and leave friends and relatives behind. The mere existence of a judgment lien — the first step toward seizing a home—can be an obstacle to selling or refinancing a home or financing repairs to it.25

Table 2 lists the states that fall into each category. See our Rating Criteria for details and our State Summaries for state-by-state information.

Best states:

Sixteen jurisdictions receive an A rating because they protect at least the median value of a home. Nine of these jurisdictions protect the family home regardless of value: Arkansas, District of Columbia, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Dakota, and Texas. All of these jurisdictions except the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico place limits on the number of acres that the exempt homestead can include.

The remaining seven jurisdictions that achieve an A rating—California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Rhode Island, and Washington26—have a dollar cap on the amount of the homestead exemption, but the cap is high enough so that a median-priced home in that state is exempt.

Worst states:

Twenty-one jurisdictions—Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming—rate an F. These states protect less than 25% of the median home value in their state. These states rate an F. Their exemption amounts are so small that they are likely to save only a heavily mortgaged home.

Seven of this final group of states—Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—are an especially deserving of an F grade because they provide no realistic protection at all for the family home. Pennsylvania, for example, provides a wildcard exemption of just $300. The debtor can apply this exemption to a car, household goods, a home, or other property. Delaware allows the head of a household to apply a $500 wildcard exemption to the family home. Only if the debtor files bankruptcy is a realistic homestead exemption ($125,000) available, but even that is less than half the median home value in the state. New Jersey provides no exemption at all that can be applied to a home. Maryland provides a $6,000 homestead exemption; Kentucky and West Virginia allow $5,000; and Michigan’s exemption is just $3,500.

Elders who have lived in a home a long time and have paid down their mortgages are particularly likely to face loss of their homes in states that have low homestead exemptions. The reason is that a creditor’s ability to force the sale of a home typically depends on whether the debtor’s equity in it is less than the exemption amount. Accordingly, a home with a large mortgage debt may be exempt even if the home’s market value would exceed the exemption amount. The reason is that, if the creditor forced the sale of a mortgaged home, the proceeds would go first to pay off the mortgage debt and only the amount left after that would go toward the creditor’s debt. By contrast, an older homeowner may have a low mortgage balance or no balance, so will be more vulnerable to a forced sale of the home.

Some states—even some states that provide little or no other protection for the home—recognize a doctrine called “tenancy by the entireties” under which a home owned by a married couple cannot be subjected to a forced sale by a creditor unless both spouses owe the debt. This legal doctrine protects some homes, but it has limited application since often both spouses owe the debt. In addition, it provides no protection at all to widows, widowers, and divorced or single parents who incur debts, even though they may be most in need of protection.

As noted above, some states protect the debtor’s home regardless of its value, usually with a limit on acreage, such as a half-acre in an urban area or 160 acres in a rural area. This approach most clearly recognizes the importance of the home. However, this approach has engendered controversy because of occasional attempts by wealthy individuals to shield all their assets from creditors by moving to one of these states and investing all their assets in an exempt home. While these cases are exceedingly rare, they may have made states reluctant to adopt uncapped homestead exemptions. NCLC’s Model Family Financial Protection Act provides a homestead exemption tied to the median home price in the state.

Exempting the family home does not leave the creditor empty-handed. Typically, homestead exemption laws are structured so that a judgment creditor—a creditor that has obtained a court ruling that the debtor owes a specific sum—can place a lien on the family home. Some states preclude execution on this lien (that is, they prevent the judgment creditor from forcing a sale of the home). However, when the family sells the home, the creditor can take any proceeds that exceed the exempt amount. The creditor may even be able take the exempt amount if the debtor does not use the sale proceeds promptly to buy a new home. Alternatively, if the home is not sold while the judgment debtor is alive, the creditor is paid when the homeowners die.

The Family Car: Can A Debtor Continue to Get to Work?

For many workers, a car is essential to employment. Many wage earners have to work substantial distances from their homes. Public transportation may be unavailable, so infrequent that it is difficult to use, or closed on evenings and weekends when they need to work. Even those whose jobs are near public transportation may be unable to work unless they have a car to take children to and from daycare.

Loss of a car can place a family on a downward trajectory that leads to job loss and a cascade of unpaid utility bills, deferred medical care, unpaid rent, and eviction or foreclosure. The effect of allowing creditors to seize the family car has wide ramifications, hurting not just the consumer and the consumer’s family but also the consumer’s landlord, the local utility provider, and other creditors that the consumer would like to pay.

Table 3 lists the states that fall into each category. The ratings for AL, AR, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, ME, MD, MA, MS, MO, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, ND, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, VT, VA, WA, and WV are based in whole or in part on use of a wildcard (an exemption that can be used to protect items of the debtor’s choice). See our Rating Criteria for details and our State Summaries for state-by-state information.

NCLC’s Model Family Financial Protection Act gives a debtor a $15,000 exemption for a car. This is considerably less than the average retail price, $25,410,27 for a used vehicle. However, since that average is based on all vehicles, reducing it to $15,000 is a reasonable way to approximate the average price for a low- or mid-priced vehicle that a struggling debtor is more likely to be driving. We have therefore used $15,000 as the standard for an A rating.

In states that provide wildcard exemptions, there are complexities in evaluating whether a state meets this standard. A wildcard is an exemption that is not earmarked for a particular category of property. Instead, the debtor has some choices about which property to apply it to. For example, Illinois provides a $2,400 exemption for a car and a $4,000 wildcard exemption, but no exemption for a bank account or household goods. A debtor could use the $4,000 wildcard to increase the protection for the car to $6,400, or to protect some household goods or a basic amount in a bank account.

To treat these wildcards in a uniform way so that state-to-state comparisons are possible, in this report we assume that any wildcard is used first to increase the exemption for a car to as close to $15,000 as possible. If there is any remaining amount, it is used to protect a small bank account, and then any remainder after that is used to protect household goods (However, if the wildcard is at least $3,000 and there is no other protection for a bank account or household goods, we have set aside $1,000 of it for those purposes). If the state makes the wildcard available only to a debtor who does not claim a homestead exemption, this report treats it as available. Details and specifics about these protocols are found in our Rating Criteria.

Best states:

Only six jurisdictions—Kansas ($20,000), Nevada ($15,000), New Hampshire ($10,000 plus all of one wildcard and part of a second), North Dakota ($2,950 plus all of one wildcard and part of a second), Puerto Rico (if the car is needed for work), and Texas (through use of a wildcard)—preserve a $15,000 vehicle from seizure by creditors. These jurisdictions receive an A rating. Several other states, such as Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Minnesota, protect a car worth $15,000 or more, but only if the car is specially modified for use by a disabled person (or, in the case of Massachusetts, if the debtor is elderly).

Worst states:

Six jurisdictions—Arkansas ($500), Delaware ($500), Michigan ($1,000), New Jersey ($1,000), Pennsylvania ($300), and the Virgin Islands ($0)—provide no realistic protection for a family’s car and are rated F. In four of these states, an exemption of $1,000 or less is all that is available to protect not just the debtor’s car but also any other personal property the debtor owns, including household goods (and in the case of Pennsylvania the debtor’s home as well)

Protecting a Basic Amount in a Bank Account

Even if a state’s exemption laws protect a debtor’s wages, home, and car, a debtor needs access to a basic amount of cash to commute to work, buy groceries, and make the upcoming rent or mortgage payment or the next payment on the family car. A debtor who is left without cash may also be unable to pay for transportation, daycare, utility service, and other necessities. An additional cushion is necessary to handle irregular expenses such as car repairs and medical expenses, potential income shocks such as unemployment or a cut in hours, and savings needed for retirement.

Every state except Delaware gives a creditor the right to seize funds in a bank account in the debtor’s name once the creditor has obtained a judgment from a court determining that the debtor owes a debt. Many states allow the creditor to clean out the account completely, protecting at most a few special types of accounts such as college savings accounts or a few types of funds, such as state benefits. Only a few states set a fixed amount that the creditor cannot touch.

The protections in CA, CT, DE, MA, NV, NY, and WA have the additional strength of being self-executing in whole or in part.

Table 4 lists the states that fall into each category. The ratings for AL, DC, FL, IL, MD, MS, NE, NV, NH, NM, NC, ND, OR, SD, TN, VA, and WA are based in whole or in part on use of a wildcard (an exemption that can be used to protect items or the debtor’s choice). See our Rating Criteria for details and our State Summaries for state-by-state information.

Protecting bank accounts is particularly important in light of the growing practice by employers to pay wages electronically through direct deposit. If a creditor can clean out the debtor’s bank account, this can amount to seizure of 100% of the debtor’s wages, in effect nullifying the federal and state limits on wage garnishment. Some state wage garnishment laws are interpreted to protect wages even after they are deposited in a bank account, but typically these laws are not self-executing: the debtor must go to court and present evidence tracing the funds on deposit to specific wage deposits. Many debtors will not know about this protection, and even if they do, this process can take weeks and will be daunting for many debtors. In the meantime, the account is frozen so the debtor cannot pay the rent, transportation, car payment, or mortgage payment, and any outstanding checks will bounce. The resulting overdraft fees that will be imposed when the next paycheck is deposited are likely to undermine the debtor’s ability to pay the next month’s bills, creating a rapid downward spiral.

The same result can occur for day laborers and workers in the gig economy. In many states, their earnings are not protected by the wage garnishment laws. If those earnings are deposited into a bank account, the entire amount is vulnerable to seizure by a creditor.

The Importance of Self-Executing Protections

Legal protection on paper is meaningless if it does not apply in practice. Self-executing protections, which do not rely on a debtor knowing the law or having access to an attorney, are the best way to ensure that the law is enforced.

In 2010, a group of federal agencies led by the U.S. Treasury Department addressed the problem of protecting federal benefits, such as Social Security, that are direct-deposited into the beneficiary’s bank account. Even though federal law makes Social Security and other similar federal benefits immune from garnishment for most purposes except child support, creditors were seizing those funds once they were deposited. To reverse the seizure of the benefits, the beneficiary had to navigate the court system and prove the source of the funds. In the meantime, the beneficiary had no access to these essential benefits, and any checks the beneficiary had written—for rent or anything else—were bouncing.

In 2010, the Treasury Department adopted a rule that requires a bank that receives a garnishment order to determine whether the bank account contains electronically deposited exempt federal benefits. If it does, the bank must protect the last two months of those deposits.29

The beauty of the Treasury rule’s protection is that it is self-executing. The bank protects the funds. No action on the part of the beneficiary is necessary—the beneficiary does not have to know their rights, file papers in court, attend court hearings, or present evidence about the source of the funds. The account is not frozen while the beneficiary tries to navigate the judicial system.

At least six states—California, Connecticut, Nevada, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington—have taken the Treasury rule’s approach and applied it to all bank accounts, creating a self-executing protection for a specified amount ranging from $400 in Nevada to $3,600 in New York, and Delaware bans bank account garnishment altogether. A self-executing protection for a specified dollar amount, without regard to the source of the funds, ensures that the exemption will achieve its purpose of protecting the debtor, saves time and money for the legal system, and relieves banks of the need to do complicated accounting or assist the debtor in tracing the source of the funds. These states serve as models for the nation in how to make an exemption for a bank account effective in achieving its goal of protecting the funds that families need to survive.

How the States Rate

Our analysis of states’ protection of bank accounts is from the point of view of a debtor who is supporting a family and renting a home or apartment. When a family’s bank account is cleaned out, that often means that the rent money is gone, as well as the money the family set aside for other essential monthly bills and future needs.

Some states provide a targeted exemption for a bank account, while others provide a wildcard that can be used to protect a bank account. When a state takes the wildcard approach, we have assumed, for purposes of uniformity, that the debtor will apply the wildcard first to the extent necessary to protect a car, and then, if possible, will protect a basic amount in a bank account. However, some states provide wildcards that can only be used for tangible personal property, not for a bank account, and some states provide no means at all to exempt a basic amount in a bank account. Table 4 describes how we applied wildcards to bank accounts, and our State Summaries provide state-by-state explanations of how we applied wildcards and other exemptions. See Rating Criteria for more detail about how we applied wildcards.

In rating the states, we gave a state an A if it protects $3,000 or more in a bank account. However, $3,000 is a very modest protection. As the estimated median monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in 2020 in the United States is about $1,170,30 preserving $3,000 in a bank account could enable a family to pay rent, plus at least some other essential expenses, for one month. But the median rent in a metropolitan area can greatly exceed $1,100 per month, and a two-bedroom unit will be too small for many families. $3,000 is less than half of the average monthly expenses for a family of four.31 It is well below the monthly income HUD uses to define a “low income family,” and less than even the income for a “very low income family.”32 Bankrate.com recommends an emergency fund of 3 to 6 times a family’s monthly costs.33

In addition, exemption laws should protect more than one month’s worth of regular income. Families need funds for irregular expenses like car or home repairs or medical expenses. They need a cushion for income shocks like a layoff, a cut in hours, or the need to take time off for medical reasons or child or elder care. And exemption laws should not promote poverty for seniors by allowing assets and savings needed for retirement to be completely wiped out. Bankrate.com recommends an emergency fund of 3 to 6 times a family’s monthly costs.34 NCLC’s Model Family Financial Protection Act recommends an exemption for $12,000 in a bank account.

We give a state a B if it protects between $2,000 and $2,999, and a C if it either protects $1,000 to $1,999 or provides that deposited wages are protected. States that protect between $300 and $999 rate a D, and states that protect less than $300 rate an F.

Since our ratings are based primarily on the amount protected, they give only part of the picture. For example, while our rating system gives California just a C because the amount protected is less than $2,000, the self-executing nature of its protection means that, in practice, it may turn out to be just as beneficial—if not more so—to families than the exemptions in states that protect a higher dollar amount but are not automatic.

Best states:

Delaware is the top state, banning all bank garnishments. Maine, Nevada, New York,35 North Dakota, South Carolina, and Wisconsin protect $3,000 to $10,000 in a bank account through an earmarked exemption or a wildcard. We give these seven states an A rating.

Worst states:

Fourteen jurisdictions—Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Utah, the Virgin Islands, and Wyoming —rate an F. These states provide no means for a debtor to exempt any amount in a bank account or protect only a few specialized types of accounts such as college tuition accounts.

Stopping Creditors from Threatening Seizure of a Debtor’s Household Goods

Household goods usually have little resale value. Seizing them and selling them does little to pay off a debt. The costs of seizure and sale can even exceed the proceeds of the sale.

Yet, while the consumer’s household goods are of little use to the creditor, they are of enormous value to the consumer. Without beds, tables, chairs, a stove, a refrigerator, and other furniture and appliances, debtors cannot maintain a household for themselves and their dependents.

Threats to seize household goods are often merely a debt collector harassment tactic rather than an actual way of recovering debts. Yet the mere threat to take a consumer’s household goods, even when the creditor rarely or never follows through, places tremendous pressure on families. The threat can induce consumers to pay old written-off credit card and other low-priority debts rather than high-priority obligations, such as rent and utility bills.

Table 5 lists the states that fall into each category. The ratings for GA, IN, ND, and TX are based in whole or in part on use of a wildcard (an exemption that can be used to protect items or the debtor’s choice). In a number of other states, the wildcard was exhausted by applying it to a car or bank account. See our Rating Criteria for details and our State Summaries for state-by-state information.

Best states:

The strongest approach is to protect all of a consumer’s necessary household goods and appliances. Eight jurisdictions—California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Kansas, Maine (with a cap on the amount of any individual item), New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Puerto Rico—follow this approach. Two additional jurisdictions—New York and Louisiana—achieve a similar result by exempting lists of household goods that include all or almost all of the essential items a family is likely to have. We have given each of these 10 states an A rating.

Other states allow the consumer to exempt household goods up to a dollar amount. Often a wildcard—an exemption that can be applied to protect items chosen by the debtor, up to a certain aggregate dollar amount—comes into play as well. In this report we have assumed, for the sake of uniformity, that the debtor would apply any wildcard first to protect a car and a basic amount in a bank account (see our Rating Criteria, and only apply any remaining amount to protect household goods. However, debtors would have to make their own individual choices. Some states also provide a separate exemption for certain specified household items, such as beds or certain appliances, so in those states a general exemption for household goods or a wildcard exemption may stretch a little farther. We give states a B rating if they protect household goods worth $12,000 or more, a C rating if it is between $8,000 and $11,999, a D rating if it is between $2,000 and $7,999, and an F rating if the state protects less than $2,000 in household goods.

Worst states:

Fourteen jurisdictions—Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Tennessee—protect virtually none of the debtor’s household goods, and are rated F. For example, Arkansas provides a $200 exemption ($500 if the debtor is married or the head of a household), which must cover all personal property. Delaware provides just a $500 exemption for all personal property except work tools, clothing, and bedding. This shocking indifference to debtors and their families means that creditors can clean out a family’s home even though used household goods typically have little or no resale value.

Some states allow a married couple to preserve jointly-owned personal property, such as household goods or a car, from creditors if only one of the two spouses owes the debt. This rule, called “tenancy by the entireties,” ameliorates the harshness of low household good exemptions in some states, but only in the case when only one of two spouses owes the debt. It provides no help to widows, widowers, divorced parents, or single individuals who incur debts.

NCLC’s Model Family Financial Protection Act protects all the debtor’s household goods but allows the creditor to ask a court to allow sale of any item worth more than $3,000. This approach ensures that a family will not be stripped of essential items needed for daily life, yet at the same time does not protect high-cost luxury items.

Several States Made Progress Since 2020, But Much Remains To Be Done

Our 2020 report documented that no state’s protections for struggling debtors met five basic standards: protecting a poverty-level wage, a median value home, an average-priced used car, a basic amount in a bank account, and essential household goods. This is still true one year later, in 2021: not one state meets these five minimal standards.

Nonetheless, several states did make progress—in some cases, significant progress—since our 2020 report:

Arizona significantly increased its homestead exemption, from $150,000 to $250,000.36 It now protects a home worth up to 89% of the state’s median value, and rates a B instead of a C in this category. This change nudges our overall rating for the state up from a D to a C.

The amount of California’s protection of the family bank account is tied to an annually-adjusted amount set by the state Department of Social Services for use in determining eligibility for public benefits. It increased from $1,788 for 2020 to $1,826 for 2021. This change is too small to affect our rating for the state in this category, but it illustrates the importance of providing a method for updating exemption amounts to account for increases in the cost of living.

Connecticut made three important improvements to its protections, pushing our overall rating for the state up from a C to a B. First, it significantly increased its homestead exemption, from just $75,000 (barely a quarter of the median value of homes in the state) to $250,000.37 The new figure represents 86% of the median value of homes in the state, and increases the state’s rating in this category from a D to a B.

Second, the same bill doubled Connecticut’s exemption for the debtor’s car, increasing it from $3,500 to $7,000, moving from a D to a C in our ratings. That bill also added an exemption for the cash surrender value of a life insurance policy.

Third, Connecticut revised its protections for bank accounts to create an automatic, self-executing protection for the first $1,000 in the account, without requiring that it be tied to an electronic direct deposit of exempt benefits or wages.38 Although this change does not affect Connecticut’s rating in this category, it will greatly benefit low-income debtors.

Georgia amended its wage garnishment rules to limit garnishment to 15% (instead of 25%) of the debtor’s disposable earnings if the debt is for a private student loan.39 This change affects too narrow a class of debtors to affect our ratings, but will be a significant help to this subset of debtors.

Under an amended Idaho law, if the payer of an electronic deposit transmits information showing that the funds (including the exempt portion of wages) are exempt, then the bank must protect those funds automatically from garnishment.40 This amendment does not alter the state’s C rating, as it does not change the amount protected. However, it will mean that the protection is more likely to reach the families it is intended to help, and families will not see their bank accounts frozen and all their checks bouncing while they try to assert the exemption.

A Maine bill41 made major changes in several of its exemptions that push our overall rating for the state up from a C to a B. First, for a family with dependent children (and for certain other debtors), it increased the state’s homestead exemption from $95,000 to $160,000, moving the state’s rating in this category from a D to slightly below a B.

The same bill creates a $3,000 exemption for the debtor’s bank account, changing the state’s rating from an F to an A in this category, a major improvement for struggling families in the state. While the bill does not address whether the protection will be automatic, it appears that the procedures the state courts follow will make it automatic.

In addition, the bill increases the state’s earmarked protection for the debtor’s vehicle from $7,500 to $10,000, moving the state’s rating in this category from a C to a B. It also improves the state’s protection for various other items, including the debtor’s wedding ring, a modest amount of other jewelry, household goods, life insurance, personal injury judgments, and retirement funds, and increases the state’s wildcard exemption from $400 to $500. A final significant improvement is that the state now provides for automatic inflation adjustments every three years, so its exemptions will no longer be in danger of eroding simply due to the passage of time.

Montana increased its homestead exemption from $250,000 to $350,000, resulting in moving our rating from a B to an A for this category.42 This change also nudges our overall rating for the state from a high D to a low C. The new law also provides that the exemption amount will increase by 4% every calendar year after 2021, reducing the danger that the protection will be eroded by inflation.

A second Montana bill increased the aggregate exemption for household goods from $4,500 to $7,000, and the cap on any particular item from $600 to $1,250.43 The same bill increased the exemption for a car from $2,500 to $4,000. Neither of these improvements results in a change in our ratings, and there is still a lot of room for improvement in both categories, but the increases are a step forward. The state also increased the exemption for the debtor’s work tools from $3,000 to $4,500.

New York’s homestead exemption increased due to the inflation adjustments that its statute requires every three years. $179,975 (an increase of $9,150) is now exempt in high-cost counties, with similar increases for other counties, where the exemption now ranges from $89,975 to $149,975. New York still rates a D for its protection of the family home, because these exemptions represent only slightly more than 25% of median values, but at least New York’s homestead exemption is not being eroded by inflation. New York also adjusted its earmarked exemption for the family car from $4,550 to $4,825 to take account of inflation, again without affecting our rating for this category.

New York also amended its exemption laws to add an exemption for COVID relief funds.44 This is an important protection, but not one addressed by this report.

Tennessee increased its homestead exemption from $25,000 (for a debtor with a minor child) to $35,000 ($52,500 for joint debtors),45 but it still protects such a small percentage of the median home value in the state (17%) that it continues to rate an F.

Utah updated its homestead exemption for inflation as required by statute, increasing the exemption from $42,700 to $43,300. This modest increase does not affect the F rating we give Utah in this category.

Virginia amended its wage garnishment law so that it now protects 75% of wages or 30 times the federal or state minimum wage, whichever is larger, plus it continues in effect the protection of an additional $52 a week if a low-income debtor has two dependent children.46 Since Virginia’s minimum wage is $9.50 an hour, 31% more than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, this increases the protection from $344 to $432 for a minimum wage worker—a significant change that increases our rating from a D to a C in this category. This change also nudges our overall rating for the state over the line from a D to a C.

In a 2021 bill,47 the state also removed a cap on the amount protected by an automatic exemption for COVID-19 relief payments that it had created in late 2020.48

Washington amended its homestead exemption so that it now protects a home worth $125,000, or the median sale price of a single-family home in the county, whichever is greater.49 This is an enormous improvement over its previous law, which only protected a home worth $125,000 – just 32% of median home values in the state. Because the exemption is now keyed to the median sale price where the home is located, the state meets our criteria for an A rating, up from a D.

Washington also significantly improved its protection of a bank account, by making the protection of the first $1,000 automatic (the automatic protection is less – just $500 – if the debt is not a consumer debt or a private student loan).50 This amendment does not alter the state’s C rating, which is based on the amount protected, but it will mean that the protection will automatically reach the families it is intended to help, and families will not see their bank accounts frozen and their checks bouncing while they try to assert an exemption.

In addition to the states listed above, California, Colorado, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Maine, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Washington all improved their protection of debtors’ wages simply because the amount protected is tied to the higher of the state or federal minimum wage, and the state minimum wage increased. While some of these increases were small—for example, just $3.20 a week in Minnesota—Connecticut’s increase was $40 and Illinois’ was $45, enough for a budget-conscious family to pay their electric bill plus reduced-price school lunches for two children every week.51 Maryland’s increase ($22.50 a week) is significant enough to raise its rating for protection of wages from a D to a C.

These changes are detailed in the State Summaries, and an appendix to NCLC’s Collection Actions summarizes state exemption laws in more detail.52 All of these changes have been included in our ratings, even if the changes have not yet taken effect.

Recommendations

What States Can Do to Protect Family Finances

States have good reason to be concerned about protecting their residents from over-aggressive collection of judgments for consumer debts. The growing wealth gap, the high volume of collection lawsuits filed around the country,53 and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic strain families to the breaking point and will make them increasingly vulnerable to seizure of essential wages and property.

State exemption laws should:

- Protect a living wage — at least $1,000 per week, but more in high-cost states—for working debtors, including those paid as independent contractors, so that families can meet basic needs and maintain a safe, decent standard of living within the community.

- Automatically protect a reasonable amount of money on deposit so that debtors have a cushion to cover several months of basic needs such as rent, daycare, utility bills, and commuting expenses.

- Preserve the debtor’s ability to work, by protecting a working car, work tools and work equipment.

- Protect the family’s housing and necessary household goods.

- Protect retirees from destitution by restricting creditors’ ability to seize retirement funds.

- Be automatically updated for inflation.

- Close loopholes that enable some lenders to evade exemption laws. For example, states that allow lenders to take household goods as collateral enable these lenders to avoid state protections of household goods.

- Be self-enforcing to the extent possible, so that the debtor does not have to file complicated papers or attend court hearings.

Model language for states to achieve these goals is provided in the National Consumer Law Center’s Model Family Financial Protection Act.

By updating their exemption laws, states can prevent creditors and debt buyers from reducing families to poverty. These protections also benefit society at large, by helping families regain their financial footing and contribute to the economy, keeping workers in the work force, helping families stay together, reducing the demand on funds for unemployment compensation and social services, and keeping money in local communities where it will aid economic recovery.

What Congress Can Do

This report has focused on state laws, because states are the primary source of protections for debtors. But the federal government has an important role, too.

Since 1968, when the Consumer Credit Protection Act was passed, a federal law has placed a limit on how much a debt collector can take from a worker’s wages.54 This limit is shockingly low – just 30 times the federal minimum wage, or $217.50 today, not even half the poverty level for a family of four and nowhere close to protecting a living wage (Fortunately, the federal law allows states to protect more of a worker’s wages, and, as detailed earlier in this report, more than two-thirds of the states have done so). Another significant flaw in the federal law is that it provides no protection for wages after they are deposited in the worker’s bank account, even if they are direct-deposited. Thus, even that $217.50 could be seized from a bank account.

It is time for Congress to improve this basic protection. Congress should:

- Increase the federal protection against wage garnishment to $1,000 in order to protect a living wage.

- Enact a self-executing bank account garnishment protection for $12,000, so that families can cover several months of expenses in order to address income or expense shocks or preserve some funds for retirement.

Congress also writes the nation’s bankruptcy laws, and controls how the government collects its own debts. Congress should also:

- Restore the viability of bankruptcy as a fresh start by simplifying the bankruptcy process, increasing asset and homestead protections, and giving student loan borrowers and those struggling with unaffordable criminal justice fines and fees the same fresh start opportunity as others.

- Instruct the federal government to stop seizing federal safety net payments, including the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, veterans benefits and Social Security benefits to repay government debts or old child support payments owed to state governments.

About the Author

Carolyn Carter is deputy director of the National Consumer Law Center and has specialized in consumer law issues for over 30 years. She is co-author or contributing author of a number of NCLC legal treatises, including Collection Actions, Consumer Credit Regulation, and Fair Debt Collection. Previously, she worked for the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland, as a staff attorney and as law reform director, and was co-director of a legal services program in Pennsylvania. She has served as a member of the Federal Reserve Board’s Consumer Advisory Council. Carolyn is a graduate of Brown University and Yale Law School and is admitted to the Pennsylvania bar.

Acknowledgements

NCLC thanks Mary Kingsley, a Massachusetts attorney, for extensive research and analysis; NCLC attorneys April Kuehnhoff, Lauren Saunders, Michael Best, Margot Saunders, and John Rao, and NCLC Senior Utility Analyst John Howat for analysis, advice, and review; Senior Fellow Bob Hobbs for his significant contributions to the 2013 version of this report; NCLC Communications Manager Stephen Rouzer for communications support; NCLC Digital Content and Operations Assistant Moussou N’Diaye for graphic design of the web-based version of this report and Julie Gallagher for the PDF version; and NCLC Researcher Anna Kowanko for research, fact-checking, and proofreading. NCLC also thanks the Annie E. Casey Foundation, whose support of our work made this report and much more possible. The views expressed in the report are solely those of NCLC and the author.

Endnotes

1 Of the 227 million American adults who have credit reports (89% of all American adults), about 68 million had debt in collections as of 2019. Andrew Warren, Signe-Mary McKernan, and Breno Blaga, Urban Wire: Income and Wealth. Data obtained in 2020 shows approximately the same number, Breno Braga, Alexander Carther, Kassandra Martinchek, Signe-Mary McKernan and Caleb Quakenbush, Urban Institute, “Debt in America: An Interactive Map” (Mar. 31, 2021) (showing a slightly lower percentage, 29%, of what is probably a slightly higher number of American adults with credit reports, given the overall increase in the U.S. population from 2019 to 2020). Yet in the 12 month period that ended on March 31, 2021, there were just 453,438 non-business bankruptcy filings – only 0.67% of the 68 million debtors. U.S. Courts, “New Bankruptcy Filing Plummet 38.1 Percent” (May 3, 2021). Even in 2010, in the midst of the Great Recession, less than 1.4 percent of the 116.7 million American households filed bankruptcy even though 39% of households had experienced financial distress. Michael Hurd and Susann Rohwedder, RAND Corp., Effects of the Financial Crisis and Great Recession on American Households (Nov. 2010).

2 Breno Braga, et al, Debt in America: An Interactive Map (Urban Institute, last updated March 31, 2021) (reporting that in 2020, 39% of individuals with a credit report living in predominantly non-white areas had one or more debts in collection on their credit report, compared to 24% of individuals living in predominantly white areas); Consumer Fin. Protection Bur., Consumer Experiences with Debt Collection: Findings from the CFPB’s Survey of Consumer Views on Debt, 17 n.17, 18 (Jan. 2017), (44% of non-white respondents were contacted about a debt in collection, compared to 29% of white respondents). See also FINRA Investor Education Foundation, Financial Capability in the United States 2016, p. 27 (July 2016), (31% of African American respondents to the 2015 National Financial Capability Study reported being contacted by a debt collection agency in the past year, compared to 18% of all survey respondents).

3 Annie Waldman & Paul Kiel, ProPublica, Racial Disparity in Debt Collection Lawsuits: A Study of Three Metro Areas (Oct. 8, 2015); Peter A. Holland, Junk Justice: A Statistical Analysis of 4,400 Lawsuits Filed by Debt Buyers, 26 Loyola Cons. Law Rev. 179, 218 (Mar. 2014) (“Debt buyers sued disproportionately in jurisdictions with larger concentrations of poor people and racial minorities. For example, Prince George’s County has only 15% of [Maryland’s] population, yet 23% of all debt buyer complaints were filed against Prince George’s County residents.”); Richard M. Hynes, “Broke but Not Bankrupt: Consumer Debt Collection in State Courts,” 60 Fla. L. Rev. 1, 3 (2008) (concluding that “civil litigation [in Virginia] is disproportionately concentrated in cities and counties with lower median income and homeownership rates; higher incidences of poverty and crime; and higher concentrations of relatively young and minority residents”). See also Mary Spector and Ann Baddour, “Collection Texas-Style: An Analysis of Consumer Collection Practices in and out of the Courts,” 67 Hastings Law Journal 1427, 1458 (June 2016) (Texas study; finding “a somewhat higher likelihood of default judgments in precincts with a higher non-White population”). See generally National Consumer Law Center, Fair Debt Collection § 1.3.1.5 (9th ed. 2018).

4 Annie Waldman & Paul Kiel, ProPublica, Racial Disparity in Debt Collection Lawsuits: A Study of Three Metro Areas, (Oct. 8, 2015) (holding income constant, defendants living in majority black census tracts in St. Louis were 20% more likely to be subject to garnishment proceedings after obtaining a judgment).

5 2019: ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, U.S. Census Bureau, MEDIAN INCOME IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS (IN 2019 INFLATION-ADJUSTED DOLLARS).

6 Bhutta, Neil, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne W. Hsu (2020). “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 28, 2020, (documenting that, in 2019, white families, on average, had eight times more wealth than Black families, and five times more wealth than Hispanic families).

7 Id.

8 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Civilian unemployment rate.”

9 Emily A. Shrider, Melissa Kollar, Frances Chen, and Jessica Semega, United States Census Bureau, “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020” (September 14, 2021).

10 Daniel Aaronson, Daniel Hartley, and Bhashkar Mazumder, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, “The Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps” (August 2020); Jane Kim, Boston University Public Interest Law Journal, Black Reparations for Twentieth Century Federal Housing Discrimination: The Construction of White Wealth and the Effects of Denied Black Homeownership, 29 B.U. Pub. Int. L.J. 135 (2019) (estimating that, when adjusted for inflation, $120 billion invested in white wealth in 1950 dollars is equivalent to $1.239 quintillion in 2019 dollars).

11 Aaron Glantz and Emmanuel Martinez, Chicago Tribune, “Modern-day redlining: How banks block people of color from homeownership” (February 17, 2018).

12 Robert Bartlett, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the Fin Tech Era (2019).

13 Auffhammer, Maximilian, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley Energy Institute at Haas, “Consuming Energy While Black” (June 22, 2020).

14 Nathaniel Meyersohn, CNN Business, “How the rise of supermarkets left out black America” (June 16, 2020).

15 Melanie Hanson, Educationdata.org, “Student Loan Debt by Race” (July 10, 2021).

16 John W. Van Alst, National Consumer Law Center, “Time to Stop Racing Cars: The Role of Race and Ethnicity in Buying and Using a Car” (April 2019).

17 Susan K. Urahn et. al., Pew, “Who Borrows, Where They Borrow, and Why” (July 2012), (finding that Black households are more likely to have taken out a high-interest payday loan); Jeremiah Battle, Jr., Sarah Mancini, Margot Saunders, and Odette Williamson, National Consumer Law Center, “How Land Installment Contracts Once Again Threaten Communities of Color” (July 2016). (documenting how lenders offering predatory land installment contracts for homeownership target neighborhoods of color).

18 Ala. Code § 6-10-12; Alaska Stat. § 09.38.115; Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 703.150; Ind. Code § 34-55-10-2.5; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 4422; Minn. Stat. § 550.37(4a); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 25-1556; N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5253; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2329.66(B); S.C. Code Ann. § 15-41-30(B); Utah Code Ann. § 78B-5-503.

19 Paul Kiel and Keith Ernsthausen, ProPublica, Capital One and Other Debt Collectors are Still Coming for Millions of Americans (June 8, 2020). See also Julia Barnard, Kiran Sidhu, Peter Smith, & Lisa Stifler, Center for Responsible Lending, Court System Overload: The State of Debt Collection in California after the Fair Debt Buyer Protection Act at 2, 28-29 (Oct. 2020) (California study; finding that 27% of all collection actions end in wage garnishment).

20 See 15 U.S.C. § 1674(a) (prohibiting an employer from discharging an employee by reason of the fact that “his earnings have been subjected to garnishment for any one indebtedness,” but placing no restriction on discharge by reason of garnishment for more than one indebtedness).

21 The 2021 federal poverty level for a one-person household is $12,880 a year or $247.69 per week. See Poverty Guidelines.

22 The 2021 federal poverty level for a four-person household is $26,500 per year or $509.62 per week. See Poverty Guidelines.

23 See Living Wage calculator.

24 See Robert J. Hobbs, April Kuehnhoff, and Chi Chi Wu, National Consumer Law Center, Model Family Financial Protection Act, Appx. A (June 2012, rev. Oct. 2021).

25 See, e.g., Jay Hancock, Kaiser Health News, UVA Health System uses thousands of property liens to get money from patients (Oct. 16, 2020) (documenting how lien placed on deceased woman’s home for her now-deceased son’s medical treatment prevented her daughter from selling the home to pay for her children’s education).

26 Rhode Island falls in this category solely because of the dollar amount its statute protects. The statute has an enormous gap in that it does not apply at all when the debt is owed to a bank, another federally-insured deposit-taking institution, or a variety of financial services providers licensed in the state. R.I. Gen. Laws § 9-26-4.1.

27 Talia James and Rich Paul, “Used Vehicles Expected to Climb to Record Highs as New Vehicle Prices Stay Steady in Q2, According to Edmunds” (July 1, 2021).

28 La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13:3881(A)(8); Mass. Gen. Laws Ch. 235, § 34(16); Minn. Stat. § 550.37(12a).

29 31 C.F.R. Part 212.

30 Apartment List publishes rent estimates each month. See Data & Rent Estimates. An average of the estimated median rent for a two bedroom apartment between January through September 2021 was calculated to get the national median – $1,172.

31 Bur. of Labor Statistics, Table 3444, Consumer units of four people by income before taxes: Average annual expenditures and characteristics, Consumer Expenditure Surveys, 2019-2020 (showing that the average annual expenditures for a household of four come to $84,595 per year, which is $7,050 per month).

32 24 C.F.R. § 5.603 defines “low income family” as one whose income is no more than 80% of the median income in the area, and a “very low income family” as one whose income is no more than 50% of the median. The median income in the United States in 2021 is $79,900 per year, or $6,658.33 per month. 80% of that figure is $5,326.67, and 50% of it is $3,329.17, See Estimated Median Family Incomes for Fiscal Year (FY) 2021.

33 Scott B. Van Voorhis, “How much should you have in savings at each age?,” Bankrate.com (May 7, 2021).

34 Scott B. Van Voorhis, “How much should you have in savings at each age?,” Bankrate.com (July 31, 2019).

35 New York protects 240 times the state minimum wage, which varies depending on the size of the employer and the location within the state, with the result that the amount protected is $2,664 to $3,600. See State Summaries for details.

36 2021 Ariz. Legis. Serv. Ch. 368, § 3 (H.B. 2617), amending Ariz. Rev. Stat. §33-1101.

37 2021 Conn. Legis. Serv. P.A. 21-161 (H.B. 6466), amending Conn. Gen. Laws § 52-352b.

38 2021 Conn. Legis. Serv. P.A. 21-131 (H.B. 5372, amending Conn. Gen. Laws § 52-367b.

39 2020 Ga. Laws Act 574, eff. Jan. 1, 2021, amending Ga. Code Ann. §18-4-1.

40 2021 Idaho Laws Ch. 186 (S.B. 1131), amending Idaho Code § 11-714.

41 H.P. 542-L.D. 737, amending Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 4422.

42 Laws 2021, Ch. 442, § 1, amending Mont. Code Ann. §70-32-104.

43 Laws 2021 Ch. 539, §1, effective May 14, 2021, amending Mont. Code §25-13-609.

44 2021 Sess. Law News of N.Y. Ch. 107 (A. 6617-A) (McKINNEY’S), amending N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5205(p).

45 2021 Tenn. Laws Pub. Ch. 301(S.B. 566), amending Tenn. Code § 26-2-301.

46 Acts 2021, sp. S. 1, ch. 8, effective July 1, 2021, amending Va. Code § 34-29.

47 2021 Virginia Laws Ch. 552 (H.B. 1800).

48 2020 Virginia Laws 1st Sp. Sess. Ch. 39 (H.B. 5068), enacting Va. Code Ann. § 34-28.3.

49 2021 Ch. 290, §3, amending Wash. Rev. Code §6.13.030.

50 2021 Ch. 50, §2, amending Wash. Rev. §6.15.010. This amendment is scheduled to sunset on July 1, 2025.

51 The U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2015 Residential Electricity Consumption Survey, the most recent available, shows that the average electricity expenditure for a 4-person household is $1,701/year or $32.71 a week. Reduced-price lunches are 40 cents per lunch, See School Meal Trends & Stats.

52 The appendix is available here.

53 National Consumer Law Center, Fair Debt Collection § 1.4.9.1 (9th ed. 2018).

54 15 U.S.C. §§ 1673.